Omar Bradley

| Omar Nelson Bradley | |

|---|---|

| February 12, 1893 – April 8, 1981 (aged 88) | |

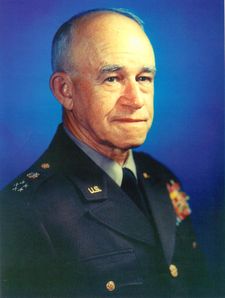

General of the Army Omar Bradley in 1950 |

|

| Nickname | "The G.I.'s General" |

| Place of birth | Randolph County, Missouri |

| Place of death | New York, New York |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery Arlington, Virginia |

| Allegiance | United States of America |

| Service/branch | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1915–1953 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | 82nd Infantry Division 28th Infantry Division U.S. II Corps First Army 12th Army Group Army Chief of Staff Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff |

| Battles/wars | World War II Korean War |

| Awards | Army Distinguished Service Medal Navy Distinguished Service Medal Silver Star Legion of Merit Bronze Star Mexican Border Service Knight Commander of the British Empire Order of Polonia Restituta Presidential Medal of Freedom Order of Suvorov Order of Kutuzov |

Omar Nelson Bradley (February 12, 1893 – April 8, 1981) was one of the main U.S. Army field commanders in North Africa and Europe during World War II, and a General of the Army in the United States Army. He was the last surviving five-star commissioned officer of the United States and the first Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Contents |

Early life and career

Bradley, the son of a schoolteacher, was born into a poor family in rural Randolph County, near Clark, Missouri. He attended country schools where his father, John, was the teacher. Bradley credited his father with teaching him a love of books, baseball and shooting. However, his father died when Bradley was 13. His mother moved to Moberly and remarried. Bradley graduated from Moberly High School in 1910, an outstanding student and captain of both the baseball and football teams. Bradley was working as a boiler maker at the Wabash Railroad when he was encouraged by his Sunday school teacher at Central Christian Church in Moberly to take the entrance examination for the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, N.Y. Bradley had been planning on saving his money to enter the University of Missouri in Columbia, where he intended to study law. He finished second in the West Point placement exams at Jefferson Barracks in St.Louis (ASVAB test). The first place winner was unable to accept the Congressional appointment, deferring instead to Bradley. While at the academy, Bradley's focus on sports prevented him from excelling academically. He was a baseball star, though, and often played on semi-pro teams for no remuneration (to ensure his eligibility to represent the academy). He was considered one of the most outstanding college players in the nation his junior and senior seasons at West Point, noted as both a power hitter and an outfielder with one of the best arms in his day. While at West Point, Bradley joined the local Masonic Lodge in Highland Falls, New York. Bradley's first wife, Mary Quayle, lived across the street when the two were growing up in Moberly and attended Central Christian Church and Moberly High School together. Moberly called Bradley its favorite son and throughout his life Bradley called Moberly his hometown and his favorite city in the world. He was a frequent visitor to Moberly throughout his career, was a member of the Moberly Rotary Club, played near handicap golf regularly at the local course and had a "Bradley pew" at Central Christian Church. When a flag project opened in 2009 in the Moberly cemetery, General Bradley and his first son-in-law and West Point graduate, the late Major Henry Shaw Bukema, were memorialized with flags in their honor from grateful citizens.

U.S. Army

At West Point Bradley lettered in baseball three times, including the 1914 team, from which every player remaining in the army became a general. He graduated from West Point in 1915 as part of a class that contained many future generals, and which military historians have called "the class the stars fell on". There were ultimately 59 generals in that graduating class, with Bradley and Dwight Eisenhower attaining the rank of General of the Army.

Bradley was commissioned into the infantry and was first assigned to the 14th Infantry Regiment. He served on the U.S.-Mexico border in 1915. When war was declared, he was promoted to captain and sent to guard the Butte, Montana copper mines.

Bradley joined the 19th Infantry Division in August 1918, which was scheduled for European deployment, but the influenza pandemic and the armistice prevented it.

Between the wars, he taught and studied. From 1920–24, he taught mathematics at West Point. He was promoted to major in 1924 and took the advanced infantry course at Fort Benning, Georgia. After a brief service in Hawaii, he studied at the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth in 1928–29. From 1929, he taught at West Point again, taking a break to study at the Army War College in 1934. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel in 1936 and worked at the War Department; after 1938 he was directly under Army Chief of Staff George Marshall. In February 1941, he was promoted to brigadier general (bypassing the rank of colonel)[1] and sent to command Fort Benning (the first from his class to become a general officer). In February 1942, he took command of the 82nd Infantry Division before being switched to the 28th Infantry Division in June.

World War II

Bradley did not receive a front-line command until early 1943, after Operation Torch. He had been given VIII Corps, but instead was sent to North Africa to be Eisenhower's front-line troubleshooter. At Bradley's suggestion, II Corps, which had just suffered the devastating loss at the Kasserine Pass, was overhauled from top to bottom, and Eisenhower installed George S. Patton as corps commander. Patton requested Bradley as his deputy, but Bradley retained the right to represent Eisenhower as well.[2]

Bradley succeeded Patton as head of II Corps in April and directed it in the final Tunisian battles of April and May. Promoted to the rank of lieutenant general, Bradley commanded the Second Corps in the invasion of Sicily.

Normandy 1944

Bradley moved to London as commander in chief of the American ground forces preparing to invade France in 1944. At D-Day, Bradley was chosen to command the US 1st Army, which alongside the British Second Army made up General Montgomery's 21st Army Group.

On 10 June, General Bradley and his staff debarked to establish a headquarters ashore. During Operation Overlord, he commanded three corps directed at the two American invasion targets, Utah Beach and Omaha Beach. Later in July, he planned Operation Cobra, the beginning of the breakout from the Normandy beachhead. As the build-up continued in Normandy, the 3rd Army was formed under Patton, Bradley's former commander, while General Hodges succeeded Bradley in command of the 1st Army; together, they made up Bradley's new command, the 12th Army Group. By August, the 12th Army Group had swollen to over 900,000 men and ultimately consisted of four field armies. It was the largest group of American soldiers to ever serve under one field commander.

Bradley's greatest triumph came when the offensive ground to a halt in the face of stiff German resistance; Bradley called in strategic air power using big bombers with huge bomb loads to attack infantry. Operation Cobra used strategic bombers (under Eisenhower's control) starting July 21, 1944. Cobra was a short, very intensive bombardment with lighter explosives before the American ground advance, so as not to create greater rubble and craters that would slow Allied progress. The bombing knocked out the German communication system, leading to confusion and ineffectiveness, opening the way for the ground offensive. Bradley sent three infantry divisions—the 9th, 4th and 30th—to move in close behind the bombing; they succeeded in cracking the German defenses, opening the way for lightning advances by armor commanded by Patton to sweep around the German lines. Several hundred Americans were killed by the bombings, including a senior general, and the use of heavy bombers in infantry operations was not repeated.[3]

Falaise Pocket

His great regret was the failure to close the "Falaise Gap." After the German attempt to split the US armies at Mortain (Operation Lüttich), Bradley's Army Group became the southern pincer in the forming Falaise pocket, trapping the German Seventh Army and Fifth Panzer Army in Normandy. Bradley on August 13, 1944, halted the advance of Patton's XV Corps beyond where Patton had been repeatedly ordered to dig in and defend. The Canadian forces were part of British General Sir Bernard L. Montgomery's 21 Army Group, Whilst many American senior commanders tended to lay blame on the British and Canadian forces for their failure to meet the American forces driving North to Falaise, it must be pointed out that the British were (as an integral part of operation Cobra) holding down the vast majority of SS panzer and higher quality Wehrmacht units thus forming the 'wheel' from which the American breakout thrust was to pivot; this is well described in Bradley's autobiography A soldier's story. The Allies failed to close the Argentan-Falaise pocket containing the almost-surrounded German forces. About 240,000 German troops (leaving almost all of their heavy material) escaped through the gap, avoiding encirclement and almost certain destruction. Bradley had assumed, incorrectly, that the Germans had already mostly escaped, and feared a German counterattack against overextended Americans (hence his orders regarding Patton's position). Bradley later admitted a mistake had been made, but blamed his superior Montgomery, as did Eisenhower, for moving the Canadians too slowly (and for using green Canadian troops instead of his veterans); Bradley's decision was largely based on mistaken information coming from Ultra, and he castigated himself primarily for relying on Ultra alone for the first time. The opportunity existed because Hitler had refused to allow his army to escape until August 16.[4] In broader perspective, Bradley, with Montgomery, had in 10 weeks destroyed the powerful German armies holding strong defensive positions and pushed the enemy back into Germany.

Germany

The American forces reached the 'Siegfried Line' or 'Westwall' in late September. The success of the advance had taken the Allied high command by surprise. They had expected the German Wehrmacht to make stands on the natural defensive lines provided by the French rivers, and had not prepared the logistics for the much deeper advance of the Allied armies. So fuel ran short.

Eisenhower faced a decision on strategy. Bradley favored an advance into the Saarland, or possibly a two-thrust assault on both the Saarland and the Ruhr Area. Montgomery argued for a narrow thrust across the Lower Rhine, preferably with all Allied ground forces under his personal command as they had been in the early months of the Normandy campaign, into the open country beyond and then to the northern flank into the Ruhr, thus avoiding the Siegfried Line. Although Montgomery was not permitted to launch an offensive on the scale he had wanted, George Marshall and Hap Arnold were eager to use the First Allied Airborne Army to cross the Rhine, so Eisenhower agreed to Operation Market-Garden. Bradley bitterly protested to Eisenhower the priority of supplies given to Montgomery, but Eisenhower, mindful of British public opinion, held Bradley's protests in check.

Bradley's Army Group now covered a very wide front in hilly country, from the Netherlands to Lorraine and, despite his being the largest Allied army group, there were difficulties in prosecuting a successful broad-front offensive in difficult country with a skilled enemy that was recovering its balance. Courtney Hodges' 1st Army hit difficulties in the Aachen Gap, and the Battle of Hurtgen Forest cost 24,000 casualties. Further south, Patton's 3rd Army lost momentum as German resistance stiffened around Metz's extensive defences. While Bradley focused on these two campaigns, the Germans had assembled troops and materiel for a surprise offensive.

Battle of the Bulge

Bradley's command took the initial brunt of what would become the Battle of the Bulge. Over Bradley's protests, for logistical reasons, the 1st Army was once again placed under the temporary command of Field-Marshal Montgomery's 21st Army Group. In a move without precedent in modern warfare, the US 3rd Army under Patton disengaged from combat in the Saarland, moved 90 mi (140 km) to the battlefront, and attacked the German southern flank to break the encirclement at Bastogne (although clearing weather allowed air superiority to relieve Bastogne and break the German offensive). In his 2003 biography of Eisenhower, Carlo d'Este implies that Bradley's subsequent promotion to full general was to compensate him for the way in which he had been sidelined during the Battle of the Bulge.

Victory

Bradley used the advantage gained in March 1945 — after Eisenhower authorized a difficult but successful Allied offensive (Operation Veritable and Operation Grenade) in February 1945 — to break the German defenses and cross the Rhine into the industrial heartland of the Ruhr. Aggressive pursuit of the disintegrating German troops by Bradley's forces resulted in the capture of a bridge across the Rhine River at Remagen. Bradley and his subordinates quickly exploited the crossing, forming the southern arm of an enormous pincer movement encircling the German forces in the Ruhr from the north and south. Over 300,000 prisoners were taken. American forces then met up with the Soviet forces near the Elbe River in mid-April. By V-E Day, the 12th Army Group was a force of four armies (1st, 3rd, 9th, and 15th) that numbered over 1.3 million men.

Command style

Unlike some of the more colorful generals of World War II, Bradley was a polite and courteous man. First favorably brought to public attention by war correspondent Ernie Pyle, he was informally known as "the soldier's general". Will Lang Jr. of Life magazine said "The thing I most admire about Omar Bradley is his gentleness. He was never known to issue an order to anybody of any rank without saying 'Please' first."

Bradley has a reputation today as a senior general who was very patient with the officers under his command, compared to his most famous colleague, George S. Patton, but the truth is far more complicated. Bradley sacked numerous generals during World War II when they displayed critical errors and bad judgments, whereas Patton actually fired only one general during the entire war, Orlando Ward.

Post-war

Veterans Administration

President Truman appointed Bradley to head the Veterans Administration for two years after the war. He is credited with doing much to improve its health care system and with helping veterans receive their educational benefits under the G. I. Bill of Rights. Bradley's influence on the VA is credited with helping shape it into the agency it is today. He was a frequent visitor to Capitol Hill, lobbying on behalf of veterans' benefits, and often testified before the committees of jurisdiction, becoming noted for his foreceful and unimpeachable support for vets.

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

Bradley served as the Army Chief of Staff in 1948. On August 11, 1949, President Harry S Truman appointed him the first Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. On September 22, 1950[5], he was promoted to the rank of General of the Army, the fifth — and last — man to achieve that rank.

Also in 1950, he was made the first Chairman of the NATO Military Committee. He remained on the committee until August 1953, when he left active duty. During his service, Bradley visited the White House over 300 times and was frequently featured on the cover of TIME magazine.

Korea

As Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Bradley was the Pentagon official in charge of the Korean War. He was the chief military policy maker during the Korean war, and supported Truman's original plan of rolling back Communism by conquering all of North Korea. When Chinese Communists invaded in late 1950 and drove back Americans in headlong retreat, Bradley agreed that rollback had to be dropped in favor of a containment of North Korea. Containment was adopted (and continues to the 21st century). Bradley was instrumental convincing Truman to fire the field commander, General Douglas MacArthur, who wanted to continue the rollback strategy after Washington dropped it.

In testimony to Congress Bradley strongly rebuked MacArthur for his support of the rollback strategy. Soon after Truman relieved MacArthur of command in April 1951, Bradley said in Congressional testimony, "Red China is not the powerful nation seeking to dominate the world. Frankly, in the opinion of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, this strategy would involve us in the wrong war, at the wrong place, at the wrong time, and with the wrong enemy."

Retirement

In retirement Bradley held a number of positions in commercial life, among them Chairman of the Board of the Bulova Watch Company from 1958 to 1973.[6]

His memoirs, A Soldier's Story, (ghostwritten by A.J. Liebling) appeared in 1951; a fuller autobiography A General's Life: An Autobiography (coauthored by Clay Blair) appeared in 1983) He took the opportunity to attack Field Marshal Montgomery's 1945 claims to have won the Battle of the Bulge. Bradley spent his last years at a special residence on the grounds of the William Beaumont Army Medical Center, part of the complex which supports Fort Bliss, Texas.

On December 1, 1965, Bradley's wife, Mary, died of leukemia. He met Esther Dora "Kitty" Buhler and married her on September 12, 1966; they were married until his death.

As a horse racing fan, Bradley spent much of his leisure time at racetracks in California and often presented the winners trophies. He also was a lifetime sports fan, especially of college football. He was the 1948 Grand Marshal of the Tournament of Roses and attended several subsequent Rose Bowl games (his black limousine with personalized CA license plate "ONB" and a red plate with 5 gold stars was frequently seen driving through Pasadena streets with police motorcycle escort toward the Rose Bowl on New Year's Day), and was prominent at the Sun Bowl in El Paso, Texas, and the Independence Bowl in Shreveport, Louisiana in later years.

Bradley also served as a member of President Lyndon Johnson's Wise Men, a high-level advisory group considering policy for the Vietnam War. Bradley was a hawk and recommended against withdrawal from Vietnam[7]

In 1970, Bradley served as a consultant for the film Patton. The film, in which Bradley was portrayed by actor Karl Malden, is very much seen through Bradley's eyes: while admiring of Patton's aggression and will to victory, the film is also implicitly critical of Patton's egoism (particularly his alleged indifference to casualties during the Sicilian campaign) and love of war for its own sake. Bradley is shown being praised by a German intelligence officer for his lack of pretentiousness, "unusual in a general".

On January 10, 1977, Bradley was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Gerald Ford.

Omar Bradley died on April 8, 1981 in New York City of a cardiac arrhythmia, just a few minutes after receiving an award from the National Institute of Social Sciences. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery, next to his two wives.[8]

His posthumous autobiography, A General's Life, was published in 1983; the book was begun by Bradley himself, who found writing difficult, and so Clay Blair was brought in to help shape the autobiography; after Bradley's death, Blair continued the writing, making the unusual choice of using Bradley's first-person voice. The resulting book is highly readable, and based on extremely thorough research, including extensive interviews with all concerned, and Bradley's own papers.[9]

Bradley is known for saying, "Ours is a world of nuclear giants and ethical infants. We know more about war than about peace, more about killing than we know about living."[10]

The U.S. Army's M2 Bradley infantry fighting vehicle and M3 Bradley cavalry fighting vehicle are named after General Bradley.

Bradley's hometown, Moberly, Missouri, is planning a library and museum in his honor. Two recent Bradley Leadership Symposia in Moberly have honored his role as one of the American military's foremost teachers of young officers. On February 12, 2010, the U.S. House of Representatives, the Missouri Senate, the Missouri House, the County of Randolph and the City of Moberly all recognized Bradley's birthday as General Omar Nelson Bradley Day. The ceremony marking the day was held at his high school alma mater and featured addresses by the current Congressional representative, Blaine Luetkemeyer, and Moberly High School Principal Aaron Vitt.

On May 5, 2000, the United States Postal Service issued a series of Distinguished Soldiers stamps in which Bradley was honored.[11]

Summary of service

Dates of rank

| No pin insignia in 1915 | Second Lieutenant, United States Army: June 12, 1915 |

| First Lieutenant, United States Army: October 13, 1916 | |

| Captain, United States Army: August 22, 1917 | |

| Major, National Army: July 17, 1918 | |

| Captain, Regular Army (reverted to permanent rank): November 4, 1922 | |

| Major, Regular Army: June 27, 1924 | |

| Lieutenant Colonel, Regular Army: July 22, 1936 | |

| Brigadier General, Army of the United States: February 24, 1941 | |

| Major General, Army of the United States: February 18, 1942 | |

| Lieutenant General, Army of the United States: June 9, 1943 | |

| Colonel, Regular Army: November 13, 1943 | |

| General, Army of the United States: March 29, 1945 | |

| General rank made permanent in the Regular Army: January 31, 1949 | |

|

General of the Army, Regular Army: September 22, 1950 |

Orders, decorations and medals

|

|

Army Distinguished Service Medal (With three oak leaf clusters) |

| Navy Distinguished Service Medal | |

| Silver Star | |

|

|

Legion of Merit (w/oak leaf cluster) |

| Bronze Star | |

| Mexican Border Service Medal | |

| World War I Victory Medal | |

| American Defense Service Medal | |

| European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with one silver and three campaign stars | |

| World War II Victory Medal | |

| Army of Occupation Medal with Germany clasp | |

| National Defense Service Medal with star | |

| British Honorary Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath | |

| Order of Polonia Restituta | |

| French Croix de guerre with palm | |

| Order of Kutuzov (1st class) | |

| Order of Suvorov (1st class) | |

| Luxembourg War Cross |

Assignment history

- 1911: Cadet, United States Military Academy

- 1915: 14th Infantry Regiment

- 1919: ROTC professor, South Dakota State College

- 1920: Instructor, United States Military Academy (West Point)

- 1924: Infantry School Student, Fort Benning, Georgia

- 1925: Commanding Officer, 19th and 27th Infantry Regiments

- 1927: Office of National Guard and Reserve Affairs, Hawaiian Department

- 1928: Student, Command and General Staff School

- 1929: Instructor, Fort Benning, Infantry School

- 1934: Plans and Training Office, USMA West Point

- 1938: War Department General Staff, G-1 Chief of Operations Branch and Assistant Secretary of the General Staff

- 1941: Commandant, Infantry School Fort Benning

- 1942: Commanding General, 82nd Infantry Division and 28th Infantry Division

- 1943: Commanding General, II Corps, North Africa and Sicily

- 1943: Commanding General, Field Forces European Theater

- 1944: Commanding General, First Army (Later 1st and 12th U.S. Army Groups)

- 1945: Administrator of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Administration

- 1948: United States Army Chief of Staff

- 1949: Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

- 1953: Retired from active service

References

Notes

- ↑ Hollister, Jay. "General Omar Nelson Bradley". University of San Diego History Department. May 3, 2001. Retrieved on May 14, 2007.

- ↑ Weigley, p.81

- ↑ James Jay Carafano, After D-Day: Operation Cobra and the Normandy Breakout (2000); Cole C. Kingseed, "Operation Cobra: Prelude to breakout." Military Review; July 1994, Vol. 74 Issue 7, p64-67, online at EBSCO.

- ↑ Blumenson, (1960) esp pp 407-13

- ↑ "GENERAL OF THE ARMIES OF THE UNITED STATES AND GENERAL OF THE ARMY OF THE UNITED STATES". http://usmilitary.about.com/library/milinfo/armyorank/blgoa.htm. Retrieved 2009-09-28. "General of the Army Omar N. Bradley, appointed Sep 22, 50. Deceased Apr 81. (General Bradley appointed pursuant to PL 957, on Sep 18, 1950.)"

- ↑ "The History of Bulova". Bulova. Retrieved on May 14, 2007.

- ↑ Frank Everson Vandiver, Shadows of Vietnam: Lyndon Johnson's wars (1997) p 327 online

- ↑ Omar Nelson Bradley, General of the Army

- ↑ Bradley, Omar; Clay Blair. A General's Life. ISBN 978-0671410247.

- ↑ Omar Bradley (1948-11-11). "Quotation 8126". The Columbia World of Quotations. Copyright © 1996. Columbia University Press.. http://www.bartleby.com/66/26/8126.html. Retrieved 2008-06-25. "The Columbia World of Quotations. 1996. NUMBER: 8126 QUOTATION: We have grasped the mystery of the atom and rejected the Sermon on the Mount.... The world has achieved brilliance without wisdom, power without conscience. Ours is a world of nuclear giants and ethical infants. ATTRIBUTION: Omar Bradley (1893–1981), U.S. general. speech, November 11, 1948, Armistice Day. Collected Writings, vol. 1 (1967)."

- ↑ "Distinguished Soldiers". United States Postal Service. Retrieved on May 16, 2007.

Bibliography

- Blumenson, Martin. "Chapter 17, General Bradley's Decision At Argentan (13 August 1944)," in Command Decisions," (1960) United States Army Center of Military History online edition

- Blumenson, Martin. The battle of the generals: the untold story of the Falaise Pocket, the campaign that should have won World War II (1993)

- Bradley, Omar N. and Blair, Clay. A General's Life: An Autobiography. 1983. 752 pp.

- D'Este, Carlo. Patton: A Genius for War (1995)

- Russell F. Weigley Eisenhower's Lieutenants: The Campaign of France and Germany 1944-1945 Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1981. ISBN 0-253-20608-1

Further reading

- Omar Nelson Bradley, The Centennial. United States Army Center of Military History. http://www.history.army.mil/brochures/bradley/bradley.htm.

External links

- Omar Nelson Bradley, General of the Army, Arlington National Cemetery profile.

- The American Presidency Project

- Omar Bradley at Find a Grave Retrieved on 2008-07-31

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Gen. George Grunert |

Commanding General of the First United States Army 1943–1944 |

Succeeded by Gen. Courtney Hodges |

| Preceded by Gen. Dwight Eisenhower |

Chief of Staff of the United States Army 1948–1949 |

Succeeded by Gen. J. Lawton Collins |

| Preceded by Adm. William D. Leahy as Chief of Staff to the Commander in Chief |

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff 1949–1953 |

Succeeded by Adm. Arthur W. Radford |

| Preceded by None |

Chairman of the NATO Military Committee 1949–1951 |

Succeeded by Lt. Gen. Etienne Baele |

| Awards and achievements | ||

| Preceded by Billy Graham |

Sylvanus Thayer Award recipient 1973 |

Succeeded by Robert Daniel Murphy |

|

|

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||